Elliott S. Dacher, M.D.

Transitions: A Guide to the 6 Stages of a Successful Life Transition

Wisdom Press, 2016 Available at Amazon (paperback or ebook) Introduction Chapter One (below) |

|

|

Shape Shifting

Long have you timidly waded, holding a plank by the shore,

Now I will you to be a bold swimmer,

To jump off in the midst of the sea, and rise again and nod to me

and shout, and laughingly dash with your hair.

—WALT WHITMAN, FROM “SONG OF MYSELF”

Now I will you to be a bold swimmer,

To jump off in the midst of the sea, and rise again and nod to me

and shout, and laughingly dash with your hair.

—WALT WHITMAN, FROM “SONG OF MYSELF”

Transitions are wonderfully troublesome times. They are as necessary for the survival and growth of soul and spirit as water and food are for physical development. The awakening of consciousness is as essential to human development as is biological evolution. Although life transitions rarely come at convenient times, they always come at the right time. They arrive to rescue us from a part of our life that has been lived to completion and deliver us to an aspect of life that is yet unknown. When we succeed in our transitions, we shift the shape of our future life.

There was once a time when community and culture carefully conveyed to the individual—through ceremony, rituals, and rites of passage—the understandings and practices of the major life transitions: youth to adulthood to elderhood. That cultural process assured smooth and predictable transition that were in accord with the framework of a given society. The individual’s life, from birth to death and beyond, was culturally and communally defined. The great transitions of life were structured and ordered. Questions such as “Who am I?” and “What is my life about?” bore no relevance. But that ancient world, with both its advantages and limitations, is no longer available to modern men and women.

We are no longer the predestined product of culturally determined roles, identities, and social customs. The center of gravity has shifted from community to individual, from ritual and social formulas to the self-developing, self-determining, self-realizing individual of modern times. We are released from the boundaries of social conditioning, social structures, and the guidance of a narrowly focused community. But released into what? For us, the questions “Who am I?” and “What is my life about?” are of great importance as well as a source of great difficulty. These are the essential questions to be asked and solved by modern men and women in the midst of the inner and outer challenges of day-to-day life.

There are two fundamental responses to this unique circumstance of modern times. The first is to fail to ask either question. In this instance, we succumb to a life that is largely set in place by the idiosyncrasies of parenting, early education, and cultural values. Such lives, more or less, run on automatic from beginning to end. For these individuals, a healthy life may be possible, but a fully awakened and experienced life is not. However, if we are truly fortunate, we can summon forth the inspiration, initiative, and courage to respond to life’s challenges by taking these questions as an ongoing process of self-discovery and self-evolution.

In the first instance, we have the example of Willy Loman, the tragic figure in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. In the character of Willy, Miller offers us a window into a modern-day life lived on automatic. Willy cannot understand, respond to, or grow into loss, aging, or the shifting circumstances of his life. Today and tomorrow are another version of yesterday. Personal growth is stunted. Adversity is met with denial, defensiveness, and reactivity. Thoreau called such lives ones of “quiet desperation.” Joseph Campbell similarly referred to them as desperate circumstances. Lacking the capacity to expand consciousness and the scope of life, such individuals wander through their days, from beginning to end, unaware of their dilemma. From the perspective of what is possible, they have squandered their lives.

Compare this to the hero stories of earlier Western literature, the stories of coming to consciousness, the stories of awakening. Whether it be the release from the enslavement in Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, the journey of Odysseus, Parsifal’s search for the Holy Grail, the Journey of Oedipus from king to pauper to wise man, or Campbell’s Hero of a Thousand Faces, we discover the character and courage of the self-determining, self-realizing individual—one who chooses personal evolution to stagnation. We see in these stories the sequential stages of transition traversed by the modern hero, and the great “boon,” as Campbell refers to it that is the fruit of this inspired and impassioned effort.

Modern individuals confront these tipping points at times of distress and suffering. They are our pivot points in modern times. They are the critical moments in which we either step up to a larger life or fall back into the old and familiar. How we relate to adversity defines the life that follows. Do we choose denial, outdated perspectives, ineffectual habituated patterns, and well-worn reactions (all of which are unconscious to the individual), or do we see adversity, distress, and suffering as gateways to a larger, awakened life?

There was once a time when community and culture carefully conveyed to the individual—through ceremony, rituals, and rites of passage—the understandings and practices of the major life transitions: youth to adulthood to elderhood. That cultural process assured smooth and predictable transition that were in accord with the framework of a given society. The individual’s life, from birth to death and beyond, was culturally and communally defined. The great transitions of life were structured and ordered. Questions such as “Who am I?” and “What is my life about?” bore no relevance. But that ancient world, with both its advantages and limitations, is no longer available to modern men and women.

We are no longer the predestined product of culturally determined roles, identities, and social customs. The center of gravity has shifted from community to individual, from ritual and social formulas to the self-developing, self-determining, self-realizing individual of modern times. We are released from the boundaries of social conditioning, social structures, and the guidance of a narrowly focused community. But released into what? For us, the questions “Who am I?” and “What is my life about?” are of great importance as well as a source of great difficulty. These are the essential questions to be asked and solved by modern men and women in the midst of the inner and outer challenges of day-to-day life.

There are two fundamental responses to this unique circumstance of modern times. The first is to fail to ask either question. In this instance, we succumb to a life that is largely set in place by the idiosyncrasies of parenting, early education, and cultural values. Such lives, more or less, run on automatic from beginning to end. For these individuals, a healthy life may be possible, but a fully awakened and experienced life is not. However, if we are truly fortunate, we can summon forth the inspiration, initiative, and courage to respond to life’s challenges by taking these questions as an ongoing process of self-discovery and self-evolution.

In the first instance, we have the example of Willy Loman, the tragic figure in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. In the character of Willy, Miller offers us a window into a modern-day life lived on automatic. Willy cannot understand, respond to, or grow into loss, aging, or the shifting circumstances of his life. Today and tomorrow are another version of yesterday. Personal growth is stunted. Adversity is met with denial, defensiveness, and reactivity. Thoreau called such lives ones of “quiet desperation.” Joseph Campbell similarly referred to them as desperate circumstances. Lacking the capacity to expand consciousness and the scope of life, such individuals wander through their days, from beginning to end, unaware of their dilemma. From the perspective of what is possible, they have squandered their lives.

Compare this to the hero stories of earlier Western literature, the stories of coming to consciousness, the stories of awakening. Whether it be the release from the enslavement in Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, the journey of Odysseus, Parsifal’s search for the Holy Grail, the Journey of Oedipus from king to pauper to wise man, or Campbell’s Hero of a Thousand Faces, we discover the character and courage of the self-determining, self-realizing individual—one who chooses personal evolution to stagnation. We see in these stories the sequential stages of transition traversed by the modern hero, and the great “boon,” as Campbell refers to it that is the fruit of this inspired and impassioned effort.

Modern individuals confront these tipping points at times of distress and suffering. They are our pivot points in modern times. They are the critical moments in which we either step up to a larger life or fall back into the old and familiar. How we relate to adversity defines the life that follows. Do we choose denial, outdated perspectives, ineffectual habituated patterns, and well-worn reactions (all of which are unconscious to the individual), or do we see adversity, distress, and suffering as gateways to a larger, awakened life?

Two Paths: Automaticity and Consciousness

Our lives generally follow one of two built-in blueprints: conditioned automaticity or awakened consciousness. The first is composed of a large group of programmed psychological perspectives and responses imprinted in our psyche early in life. They perpetuate the attitudes and styles of family and culture. This is a conservative system that seeks to maintain the status quo. It is rarely questioned. It relies on fixed ways of perceiving the world and equally fixed habitual response patterns. These fixed patterns of perception and reaction define the character of such a life.

We all know how this works. We interpret our life experience in familiar ways and respond with equally familiar reactions. Circumstances may change, but we perceive and mentally shape them to accommodate our learned and fixed templates. The default mechanism is automaticity. We wonder why we always end up in the same situation, why things just never seem to change. But there is not enough curiosity or initiative to examine the workings of the conditioned mind.

We all know how this works. We interpret our life experience in familiar ways and respond with equally familiar reactions. Circumstances may change, but we perceive and mentally shape them to accommodate our learned and fixed templates. The default mechanism is automaticity. We wonder why we always end up in the same situation, why things just never seem to change. But there is not enough curiosity or initiative to examine the workings of the conditioned mind.

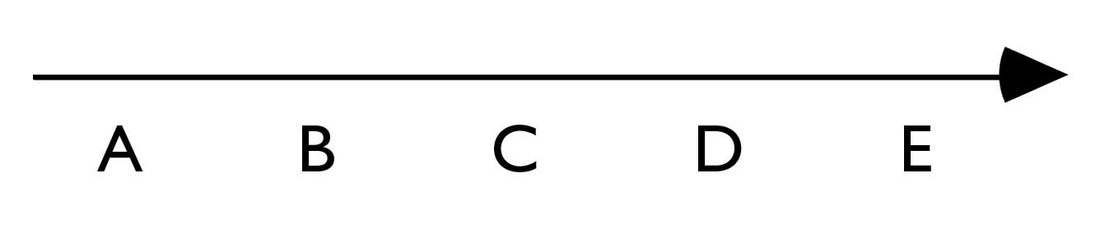

FIGURE 1. Automaticity

Point “A” on Figure 1 represents the pattern of automaticity whose sources are the perceptual and psychological patterns learned early in life. Once established, these patterns direct our lives in a straight line. However, our lives will invariably have their “bumps” (B through E above), challenges to the normal flow of life. These disruptive moments may be initiated by illness, loss, excessive stress, aging, unsatisfying success, or the disappointments associated with failure. As indicated by the arrow, irrespective of these potentially life-transforming challenges, life remains much the same. And most often, at the midpoint of an automated life, there is a downward drift of stagnation as life reaches its end point, devoid of the vitality and adaptability of a conscious life.

If we follow the path of an automated life, there is little flexibility in dealing with life’s challenges. There are only two possible responses: denial and procrastination. Either of these responses assures the continuity of an automated life. They maintain the status quo. In the first instance, we deny the existence of distress by unconsciously blocking unpleasant experiences, by avoiding or withdrawing from distress, occupying ourselves with one distraction or another, or treating distress with self-betraying transient pleasures. In the second instance, we simply wait and bear the problem at hand, perhaps trying one remedy or another, always hoping the difficulty at hand will pass by itself. In each instance, our response and its consequences are largely unconscious.

Denial and procrastination offer us a quick, though illusionary, reprieve from the normal and inevitable adversities of life. We are relieved of the necessity to examine, question, and, if required, change our lives. Life’s transitional moments will invariably be lost, and there will arise an increasing discord between how we live our life and the deeper calling of our soul. Most often this resistance to life’s natural flow and call for change shows up as a physical or emotional symptom. It is then labeled and treated by a professional with drugs of one sort or another, while its deeper source is unseen and ignored.

The second possibility, a more recent one in human existence, results from the development of the prefrontal cortex and the simultaneous emergence and evolution of human consciousness. This allows for moment-to-moment innovation, flexibility, attention to the unique circumstance of each moment, and self-inquiry. An evolving consciousness perceives and responds to life in accordance with the freshness of the moment and the actuality of the circumstance as it is. It is uninfluenced by preexisting perceptual and reaction patterns. An awakened consciousness must be chosen and cultivated. It is neither passed on at birth, nor given to us by family or culture. It emerges and matures through inner development. It is the sign of an evolved and dynamic life that utilizes the conscious capacities that have developed in the modern evolution of the human brain.

If we follow the path of an automated life, there is little flexibility in dealing with life’s challenges. There are only two possible responses: denial and procrastination. Either of these responses assures the continuity of an automated life. They maintain the status quo. In the first instance, we deny the existence of distress by unconsciously blocking unpleasant experiences, by avoiding or withdrawing from distress, occupying ourselves with one distraction or another, or treating distress with self-betraying transient pleasures. In the second instance, we simply wait and bear the problem at hand, perhaps trying one remedy or another, always hoping the difficulty at hand will pass by itself. In each instance, our response and its consequences are largely unconscious.

Denial and procrastination offer us a quick, though illusionary, reprieve from the normal and inevitable adversities of life. We are relieved of the necessity to examine, question, and, if required, change our lives. Life’s transitional moments will invariably be lost, and there will arise an increasing discord between how we live our life and the deeper calling of our soul. Most often this resistance to life’s natural flow and call for change shows up as a physical or emotional symptom. It is then labeled and treated by a professional with drugs of one sort or another, while its deeper source is unseen and ignored.

The second possibility, a more recent one in human existence, results from the development of the prefrontal cortex and the simultaneous emergence and evolution of human consciousness. This allows for moment-to-moment innovation, flexibility, attention to the unique circumstance of each moment, and self-inquiry. An evolving consciousness perceives and responds to life in accordance with the freshness of the moment and the actuality of the circumstance as it is. It is uninfluenced by preexisting perceptual and reaction patterns. An awakened consciousness must be chosen and cultivated. It is neither passed on at birth, nor given to us by family or culture. It emerges and matures through inner development. It is the sign of an evolved and dynamic life that utilizes the conscious capacities that have developed in the modern evolution of the human brain.

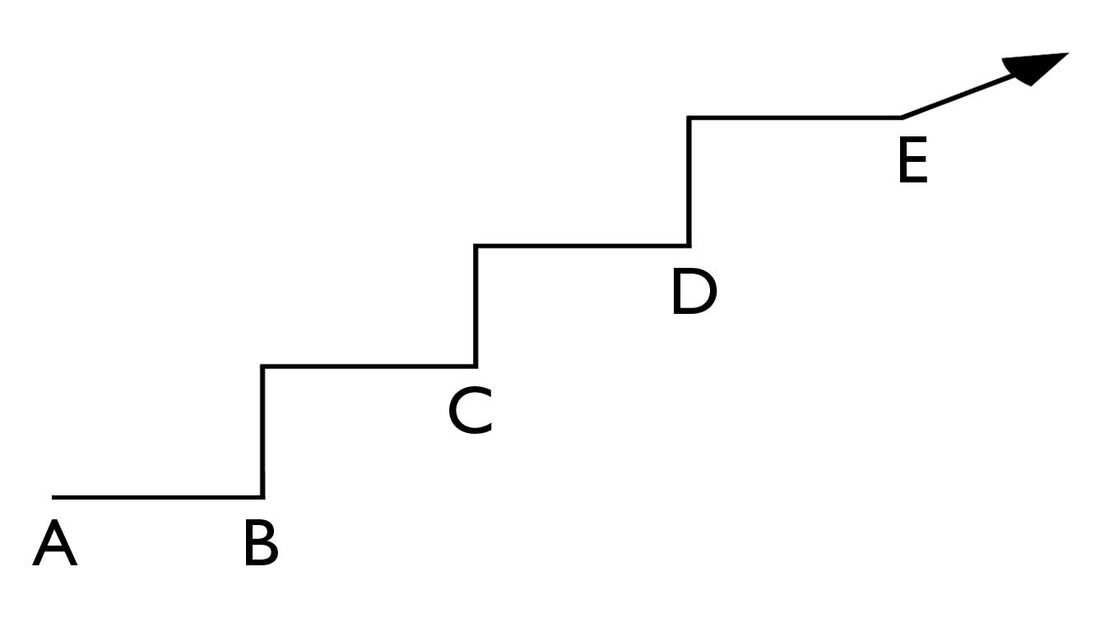

FIGURE 2. The Conscious Life

Figure 2 depicts the second path that life may take, the path of a shape shifter, the path of an awakening consciousness. As in Figure 1, it begins at point “A” where our familial and cultural conditioning defines and shapes our life, pointing it in a straight and unchanging direction. Yet, when distress and disruption occur (B through E), when life seems to stop for a moment and a crack suddenly appears in the automated routine of daily life, these individuals do not reach out for a remedy to anesthetize the tension, pain, and suffering that invariably accompanies these moments. There is no grasping at money, power, possessions, treatments, drugs, or dependent relationships. There is no denial or procrastination. Such individuals learn to love the question, “Why me and why now?”

These individuals see adversity as an opportunity to reconsider and reshape their lives. Adversity becomes a precious teacher of life. They invest in growth and development rather than the status quo. They seek a more conscious and vital life. Values, lifestyles, attitudes, and social relationships are open to reconsideration. They are available and eager to engage the stages of a life transition. The vertical lines in Figure 2 represent the transitional process initiated by the life events (B–E). Once the transitional process, the vertical leap, has brought forth a new structure and direction, there is a period of time, often lasting many years (the horizontal lines), during which these individuals fully develop the potential unleashed by the growth in consciousness that accompanied the transition process.

There is a leap in consciousness, capacity, resourcefulness, vitality, and authenticity, a growth in attention, mindfulness, and presence in life. We become increasingly free to be as we are, unchained from our past, and living in the naked truth of the moment. The light of awareness, stripped of the past, illuminates the nowness of each moment. Although the insights of an awakening consciousness may come as a sudden “aha,” there is a progressive process of incremental growth of personal freedom that underlies these sudden breakthroughs. All of this is aborted if we fall back into an automated life, failing to navigate life’s transitions.

However, this is not an all-or-nothing situation. Our lives are a mixture of automated and conscious living. Individuals who live automated lives do change and grow. They develop careers, invest in relationships, and nurture families. They are often good people living decent lives. Their growth, however, is always restrained, and their possibilities are similarly limited. It is a life, but a limited one.

One never knows when a life that runs on automatic may undergo a radical shift toward transition and change. I’ve been fooled too many times. As a result, I’ve learned to respect and hold in awe the mystery of life and its unfolding, and how love, a particular person, an unexpected revelation, or a life-threatening disease can alter the course of a life that previously followed a straight line. Because we never know, we can never pass judgment on the character, rhythm, or pace of the unfolding of another’s life.

Once experienced, future transitions lose much of their fearfulness and uncertainty. What was previously looked at with apprehension and fear can now be approached with interest and anticipation. We’ve learned to focus our attention, let go of unnecessary activities, allow for more solitude, and carefully listen to what is moving in our lives. Care, patience, sensitivity, and discerning action will allow us to move through change with greater ease. We master the skill of shape shifting—the skill of consciously reshaping our lives by successfully traversing life’s transitions, big and small. We have learned the art of shape shifting.

These individuals see adversity as an opportunity to reconsider and reshape their lives. Adversity becomes a precious teacher of life. They invest in growth and development rather than the status quo. They seek a more conscious and vital life. Values, lifestyles, attitudes, and social relationships are open to reconsideration. They are available and eager to engage the stages of a life transition. The vertical lines in Figure 2 represent the transitional process initiated by the life events (B–E). Once the transitional process, the vertical leap, has brought forth a new structure and direction, there is a period of time, often lasting many years (the horizontal lines), during which these individuals fully develop the potential unleashed by the growth in consciousness that accompanied the transition process.

There is a leap in consciousness, capacity, resourcefulness, vitality, and authenticity, a growth in attention, mindfulness, and presence in life. We become increasingly free to be as we are, unchained from our past, and living in the naked truth of the moment. The light of awareness, stripped of the past, illuminates the nowness of each moment. Although the insights of an awakening consciousness may come as a sudden “aha,” there is a progressive process of incremental growth of personal freedom that underlies these sudden breakthroughs. All of this is aborted if we fall back into an automated life, failing to navigate life’s transitions.

However, this is not an all-or-nothing situation. Our lives are a mixture of automated and conscious living. Individuals who live automated lives do change and grow. They develop careers, invest in relationships, and nurture families. They are often good people living decent lives. Their growth, however, is always restrained, and their possibilities are similarly limited. It is a life, but a limited one.

One never knows when a life that runs on automatic may undergo a radical shift toward transition and change. I’ve been fooled too many times. As a result, I’ve learned to respect and hold in awe the mystery of life and its unfolding, and how love, a particular person, an unexpected revelation, or a life-threatening disease can alter the course of a life that previously followed a straight line. Because we never know, we can never pass judgment on the character, rhythm, or pace of the unfolding of another’s life.

Once experienced, future transitions lose much of their fearfulness and uncertainty. What was previously looked at with apprehension and fear can now be approached with interest and anticipation. We’ve learned to focus our attention, let go of unnecessary activities, allow for more solitude, and carefully listen to what is moving in our lives. Care, patience, sensitivity, and discerning action will allow us to move through change with greater ease. We master the skill of shape shifting—the skill of consciously reshaping our lives by successfully traversing life’s transitions, big and small. We have learned the art of shape shifting.

Overcoming

There is an evolutionary impulse in each of us, in life itself. That is how life has evolved from the smallest life form to the complex human experience. We can experience that impulse as a nagging sense that there is more to life, a frustration with our limitations, boredom, or an inner restlessness. We may experience as a deep longing or yearning to know life at its fullest. If we nurture this impulse, it will grow and save our life, culture, and planet. It will allow for the continued growth of life toward its final maturity. That is why, as Emerson said, there is greatness in our transitions.

The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, in his book Thus Spake Zarathustra, states that it is man’s task to overcome man. This seeming paradox expresses a transcendent understanding of humankind’s life journey, an understanding that has been restated over and over by wise men and women. Nietzsche was speaking about the conscious man overcoming the automatic man.

The German poet Rainer Rilke states it another way. He says that at birth we are all given a sealed envelope that contains the mystery of life. Some of us are meant to open the envelope and live conscious lives, while others seem destined to leave the envelope unopened, living a more or less automatic life, and passing the unopened envelope to the next generation.

In Psychology and Religion Volume 11: West and East, the psychologist C. G. Jung offers a further perspective on overcoming:

The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, in his book Thus Spake Zarathustra, states that it is man’s task to overcome man. This seeming paradox expresses a transcendent understanding of humankind’s life journey, an understanding that has been restated over and over by wise men and women. Nietzsche was speaking about the conscious man overcoming the automatic man.

The German poet Rainer Rilke states it another way. He says that at birth we are all given a sealed envelope that contains the mystery of life. Some of us are meant to open the envelope and live conscious lives, while others seem destined to leave the envelope unopened, living a more or less automatic life, and passing the unopened envelope to the next generation.

In Psychology and Religion Volume 11: West and East, the psychologist C. G. Jung offers a further perspective on overcoming:

|

The difference between the “natural” individuation process, which runs its course unconsciously, and the one which is consciously realized, is tremendous. In the first case consciousness nowhere intervenes; the end remains as dark as the beginning. In the second case so much darkness comes to light that the personality is permeated with light, and consciousness necessarily gains in scope and insight.

|

Each one of us will, out of necessity, confront events that disrupt our lives. They invariably urge us toward change. Our only choice lies in deciding what we do with these challenges. Do we maintain a fixed and unchanging life, living on automatic, or do we step up to a life based on an awakening consciousness? Do we choose to carry the outdated past into the future, or do we discover a larger life permeated with light? The choice is ours. And that choice will determine the character and fate of our one precious lifetime.

HEART ADVICE FROM A FELLOW TRAVELER

1. I am certain that what enabled me to move through my first major transition was the knowledge and inspiration acquired from others who had gone before and left a precise roadmap for others to follow.

Although I knew that the passage could only be done alone, in a sense I never felt alone. I always felt the presence of the great myths and stories, of yesterday’s life explorers.

At the most difficult moments, I was able to take stock of my situation and compare it to these roadmaps to see if I was going in the correct direction. When I craved solitude and time alone, I wanted to be certain I was not withdrawing or pushing people away, but rather doing the positive work of transition. When I questioned my sanity, it was of great value to know that others had taken this road before me and that they were quite sane. When I ran into difficulties and challenges, it was essential to know that these were the natural experiences of transition, difficulties that were to be expected. And in the darkest hours, I was assured by the great stories that the light would follow. Having a roadmap gave me wise guidance, hope, and faith that carried me through.

Could Homer have written the Odyssey, Sophocles the Oedipus trilogy, or Wolfram von Eschenbach the tale of Parsifal had they not each known the way of consciousness? Whatever the culture, language, or age, the story remains the same. I always found this comforting, and, during the darkest hours, I read and reread these great tales. There are other books I would suggest, books that inspire and reassure during difficult times. These include: Rainer Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha, Alexander Daumal’s Mount Analogue, and Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. Put them in your knapsack and carry them with you. They are good nourishment when one’s soul gets hungry.

2. A note of caution: impulsiveness is not helpful. We each have assumed obligations and responsibilities in our lives. It is important to conclude these with care and honor. Although there are times when one must just stop and get off, these times are rare. If impulsiveness is not helpful, neither is procrastination. What we are seeking is a balanced and thoughtful reexamination of our lives, a careful and timely consideration of the choices at hand.

Some transitions are predictable: for example, separation and divorce, the empty nest, and a midlife transition When you see them coming, you can begin the inward turn one to two years ahead of time, contemplating the change, exploring the intention of this next part of life, reading, and, yes, planning. Other experiences, like the sudden onset of disease or loss, may thrust you directly into transition. In either instance, it is important to be careful, discerning, and wise about the movement into transition and the care of existing responsibilities.

3. We will surely encounter confusion and doubt in our transitions. It is important to identify and acknowledge these feelings as they arise. They are part of our human condition. We note their presence rather than judge ourselves, and let them go rather than attach to them. We are usually taken over by our thoughts and emotions. We identify with them so tightly that we believe we are those thoughts and feelings. Nothing could be more false and damaging than this mistaken belief. We acknowledge all thoughts and feelings that arise during transitions—pleasant and unpleasant—as part of our experience, but they are not who we are.

4. In the midst of change, it is best to find a way to live with some level of stability. Eating well, exercising, creating a comfortable living space, visiting familiar parks, following familiar routines, and maintaining and nurturing healthy friendships. These activities will be quite useful in an otherwise destabilizing time.

But there is one more critical way we can stabilize ourselves during times of change. Meditation is one of the surest ways to achieve this goal. In the natural stillness of our mind, we can experience the part of ourselves that is eternal and unchanging, strong and wise. When we make contact with this aspect of self, we feel at ease, confident, and assured. However turbulent or ephemeral our outer circumstances may seem, we can always count on its stability. Our inner self is a refuge from the storm and an assurance of the continuity of a place of peace and well-being that is always found within.

5. At times of transition, we often need assistance from others. Support can be quite helpful when wisely chosen. Choose an individual who has walked that path in his or her own life, an individual with integrity, wisdom, patience, generosity, and an open heart. It is important to know if that person has teachers of his or her own, and if that person follows a tradition whose aim is personal development and freedom. Take a close look at this individual and his or her students. Choose well. And be comfortable with shifting teachers when it seems appropriate.

Although I knew that the passage could only be done alone, in a sense I never felt alone. I always felt the presence of the great myths and stories, of yesterday’s life explorers.

At the most difficult moments, I was able to take stock of my situation and compare it to these roadmaps to see if I was going in the correct direction. When I craved solitude and time alone, I wanted to be certain I was not withdrawing or pushing people away, but rather doing the positive work of transition. When I questioned my sanity, it was of great value to know that others had taken this road before me and that they were quite sane. When I ran into difficulties and challenges, it was essential to know that these were the natural experiences of transition, difficulties that were to be expected. And in the darkest hours, I was assured by the great stories that the light would follow. Having a roadmap gave me wise guidance, hope, and faith that carried me through.

Could Homer have written the Odyssey, Sophocles the Oedipus trilogy, or Wolfram von Eschenbach the tale of Parsifal had they not each known the way of consciousness? Whatever the culture, language, or age, the story remains the same. I always found this comforting, and, during the darkest hours, I read and reread these great tales. There are other books I would suggest, books that inspire and reassure during difficult times. These include: Rainer Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha, Alexander Daumal’s Mount Analogue, and Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. Put them in your knapsack and carry them with you. They are good nourishment when one’s soul gets hungry.

2. A note of caution: impulsiveness is not helpful. We each have assumed obligations and responsibilities in our lives. It is important to conclude these with care and honor. Although there are times when one must just stop and get off, these times are rare. If impulsiveness is not helpful, neither is procrastination. What we are seeking is a balanced and thoughtful reexamination of our lives, a careful and timely consideration of the choices at hand.

Some transitions are predictable: for example, separation and divorce, the empty nest, and a midlife transition When you see them coming, you can begin the inward turn one to two years ahead of time, contemplating the change, exploring the intention of this next part of life, reading, and, yes, planning. Other experiences, like the sudden onset of disease or loss, may thrust you directly into transition. In either instance, it is important to be careful, discerning, and wise about the movement into transition and the care of existing responsibilities.

3. We will surely encounter confusion and doubt in our transitions. It is important to identify and acknowledge these feelings as they arise. They are part of our human condition. We note their presence rather than judge ourselves, and let them go rather than attach to them. We are usually taken over by our thoughts and emotions. We identify with them so tightly that we believe we are those thoughts and feelings. Nothing could be more false and damaging than this mistaken belief. We acknowledge all thoughts and feelings that arise during transitions—pleasant and unpleasant—as part of our experience, but they are not who we are.

4. In the midst of change, it is best to find a way to live with some level of stability. Eating well, exercising, creating a comfortable living space, visiting familiar parks, following familiar routines, and maintaining and nurturing healthy friendships. These activities will be quite useful in an otherwise destabilizing time.

But there is one more critical way we can stabilize ourselves during times of change. Meditation is one of the surest ways to achieve this goal. In the natural stillness of our mind, we can experience the part of ourselves that is eternal and unchanging, strong and wise. When we make contact with this aspect of self, we feel at ease, confident, and assured. However turbulent or ephemeral our outer circumstances may seem, we can always count on its stability. Our inner self is a refuge from the storm and an assurance of the continuity of a place of peace and well-being that is always found within.

5. At times of transition, we often need assistance from others. Support can be quite helpful when wisely chosen. Choose an individual who has walked that path in his or her own life, an individual with integrity, wisdom, patience, generosity, and an open heart. It is important to know if that person has teachers of his or her own, and if that person follows a tradition whose aim is personal development and freedom. Take a close look at this individual and his or her students. Choose well. And be comfortable with shifting teachers when it seems appropriate.

Copyright © 2016 by Elliott S. Dacher, M.D. (From Transitions: A Guide to the 6 Stages of a Successful Life Transition, Wisdom Press, 2016)